Fifty Years Later and Still Searching for Answers

There are bone fragments. Sometimes teeth. Maybe a metal button from a scrap of clothing. A lot of this sits in boxes in office buildings in Santiago. Some, the few that have been identified, are buried in gravesites or treasured as memorials by family members. But most people have nothing.

I’m talking about the disappeared in Chile. And, of course, elsewhere. People who were picked up by their own government, detained, tortured, likely killed, all without ever being officially recognized. No charges, no convictions, no record of their existence.

In Chile, following the military coup that took place 50 years ago today, anyone suspected of supporting the leftist government of Salvador Allende, who had been democratically elected as his nation’s president three years earlier, was summarily rounded up and taken in for questioning. Certainly all official government workers, but also those active in their trade unions, miners, factory workers, peasants, and students. Sometimes it was just people who looked a certain way, had certain books in their possession, who listened to folk music.

If these people were extremely lucky, they would be released within hours or days of being questioned, maybe with threats, maybe bearing bruises. There was another category of people whose detentions continued, often thanks to bogus claims like being a “traitor to one’s country,” but who could be considered lucky nonetheless because at least they were officially recognized. At least, the regime acknowledged that they were in their custody, acknowledged their existence.

Those people — the tens of thousands who suffered horrible abuse and who were often jailed for years for nothing more than their beliefs — were lucky because their official detention meant they would most likely live. Once General Augusto Pinochet’s regime admitted to having someone, the chances they would kill them went way down. So while those people didn’t have their freedom, they often had their lives.

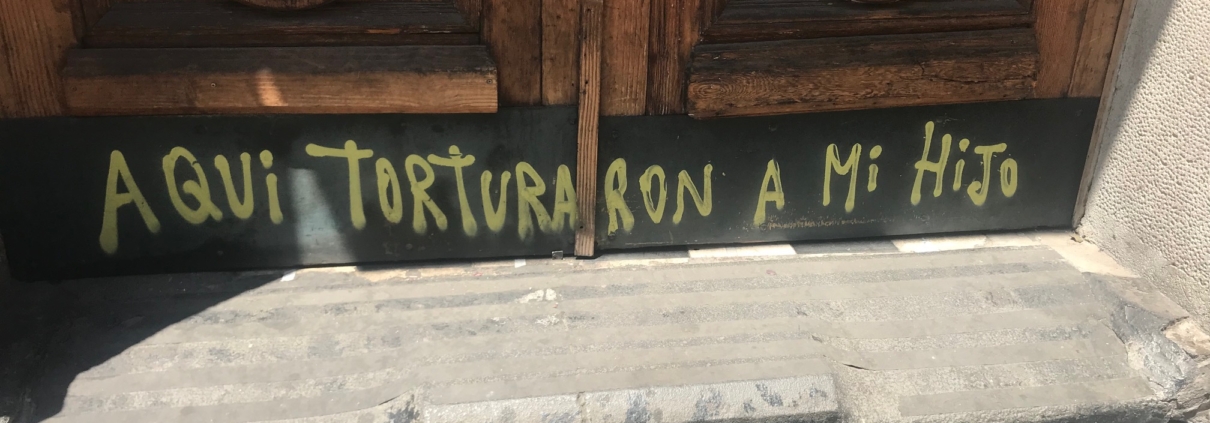

But then, there were the unlucky. Those who were killed, obviously, more than 3,200 of them. But also the men, women, and sometimes children who simply disappeared. Who didn’t return home one day after work or school, snatched off the street, often in broad daylight. They’d be blindfolded and taken to any of the clandestine torture centers springing up from the northern crown of that narrow nation down to its southern tip. Torture centers housed in old villas, on naval ships, in random apartments right in the center of its most populated city. From the Atacama Desert in the north, which has the distinction of being the driest place on earth, to the desolate islands in the south that mark the route to Antarctica like breadcrumbs.

When their loved ones would go to the authorities, to file a missing person’s report or ask after the whereabouts of their sons, daughters, parents, spouses, the police and the military would feign ignorance. Sometimes they were ignorant, of course, since it was General Pinochet’s secret service, the DINA, who were guilty of the most heinous crimes. But not only did the police fail to share information with loved ones, they also failed to share sympathy. Often, they’d guess at one’s vulnerability and exploit it … “Maybe your husband has left you for someone more beautiful,” to a distraught but homely wife. Or “Are you sure your daughter didn’t get pregnant and run off with that boyfriend of hers?” to the most pious father.

Mothers left clutching photographs, hanging up signs describing their missing child, what they were wearing, where they were last seen, much the way New Yorkers did after our own September 11th. For many, those photographs are all they’ll ever have.

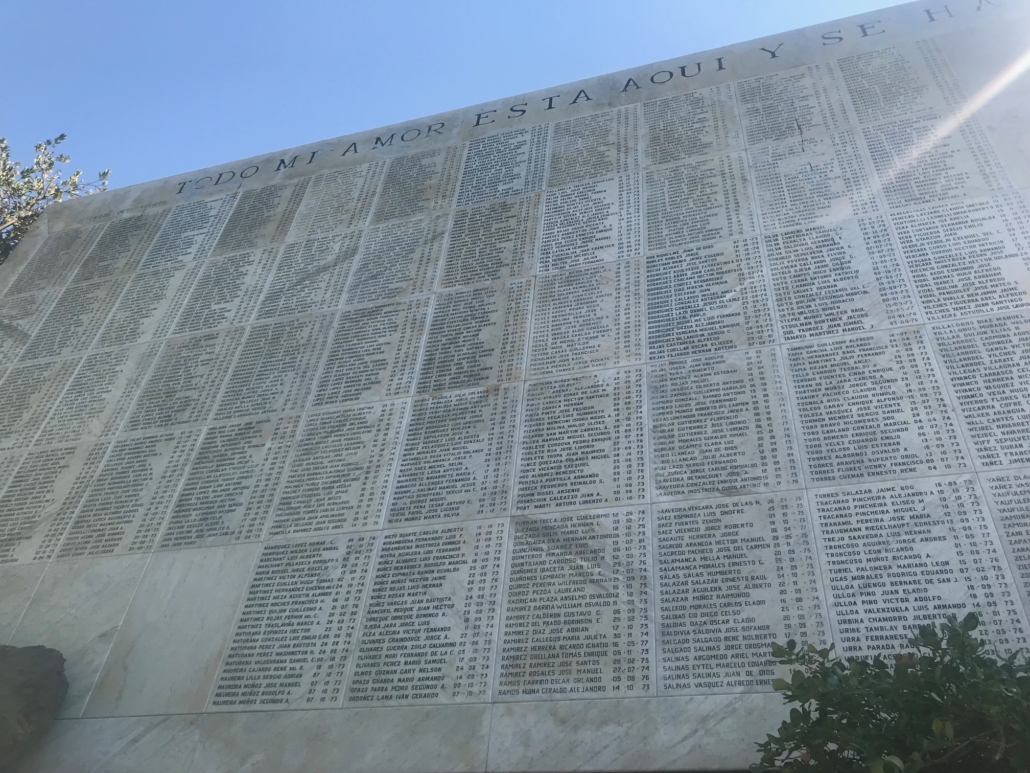

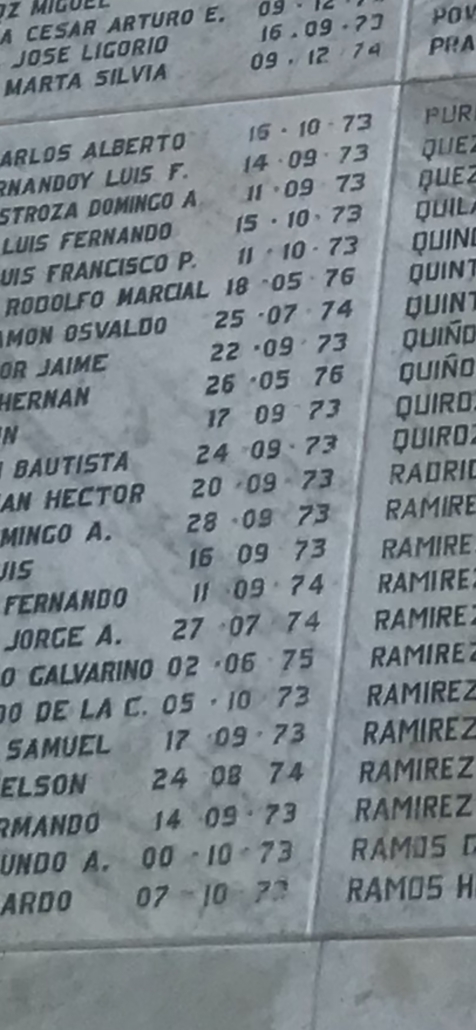

A lot of people were killed during the seventeen years that Pinochet ruled Chile with an iron fist. Most of the more than 3,200 official deaths occurred in the first year of the regime and most of those occurred in the first three months. The dates on the memorial in Santiago’s General Cemetery skew heavily toward September, October, and November 1973.

Perhaps those dates skew so early because in the beginning, when martial law was declared and a wartime mentality descended on the once peaceful nation, the military openly killed people in the streets, leaving bodies to float down the Mopocho River that runs right through the capital city. But Pinochet and his henchmen wouldn’t act so brazenly for long.

The international community was watching and the regime’s extrajudicial murders moved underground … or high in the sky.

In November 1978, the bodies of fifteen missing men were found in an abandoned limekiln 25 miles west of Santiago. Pinochet was not happy with the discovery nor the subsequent investigations, and ordered the military to dig up the bodies of hundreds of others they’d killed and move them … to the ocean, the desert, the mouths of volcanos. Incinerate them, blow them up with mines, drop them out of helicopters, anything to ensure that their remains would not be found and would not be linked to Pinochet’s government.

Chile’s President Gabriel Boric recently announced a new statewide effort to search for and identify remains. It won’t be easy and, to many, it may feel like too little too late. Nearly 1,500 people are still considered disappeared. And remains have been identified of just 307. But it’s something, a step, a gesture, an opportunity for closure perhaps.

Because imagine the mothers and fathers, the husbands and wives and siblings and friends, who know they weren’t abandoned, who know that their loved ones didn’t up and leave them of their own free will. They started with desperate searching and desperate hoping and vows to never stop looking. But days turned into weeks turned into years turned into decades.

And now, half a century has passed since that fateful day in Chile when everything changed. And the families of the disappeared just want answers.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!