“It Can’t Happen Here”

They believed their democracy would stand. And then it fell.

On June 29, 1973, army tanks rolled down the wide avenues of Santiago de Chile. It was a Monday morning, just after 9, and the streets and sidewalks of the capital city were full of people on their way to work and school. A rogue element of the military was attempting to overthrow the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende.

The coup was stopped within a couple of hours, when military leaders who remained loyal to the Constitution swooped in and put a quick end to it. But the attempt would have consequences, thanks largely to the critical information it revealed: Who supported the legitimate government and who didn’t, which members of the military would uphold their oath of political impartiality and which wouldn’t, and, most ominously, the exact location of the government’s weaknesses when faced with insurrection.

The leaders of the coup attempt took the information they gleaned and went back to regroup, while the people of Chile went on their way. Did they know that tensions were high in their country? Yes, of course. Tensions had been rising for several years and seemed to have hit a boiling point. Were they angry and concerned? Yes, without question. There’d been protests and counter-protests, demonstrations and counter-demonstrations, and increasing numbers of clashes and street fights between the two sides over the course of that year. Did they believe that something drastic might happen, that something big was about to take place because the country simply couldn’t continue on the path it was on? Yes, they were sure of it. Many predicted there would be another coup attempt that would force the resignation of Allende and hasten the election of a new president.

But they never imagined that the successful coup that would come ten weeks later, on Tuesday, September 11, would install a military regime with a brutal dictator who would rule what had once been the longest-lasting, most stable democracy in South America for the next seventeen years.

I’m not saying that’s what will happen here. The differences between the situation in Chile in the 1970s and the one in the United States right now are numerous enough to fill a library. The nations’ histories are different, the political players are different, the circumstances are different not least because of the U.S. intervention, orchestration and funding of the Chilean coup.

Not to mention that, there, President Allende was a victim of the coup. Whereas, here, President Trump would be its beneficiary.

But there is one truth that we Americans would do well to focus on: The Chilean people believed deeply in their country, they believed their government was strong enough to withstand a “little” insurrection, that their democratic institutions would protect them from the atrocities that happened elsewhere. Those things couldn’t possibly happen here.

And then they did.

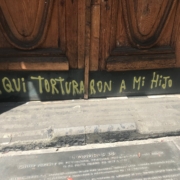

Even after the coup took place, after the military regime installed itself in the houses of government, after the nightly curfews and daily arrests began, they still believed it would all be okay. They told one another that this was brief, a “soft coup” like those that had swept their continent, that order would be restored, that elections would be held and a new president would be elected, and that this dark period would be behind them. They told that to each other. And they told that to themselves.

And they were wrong.

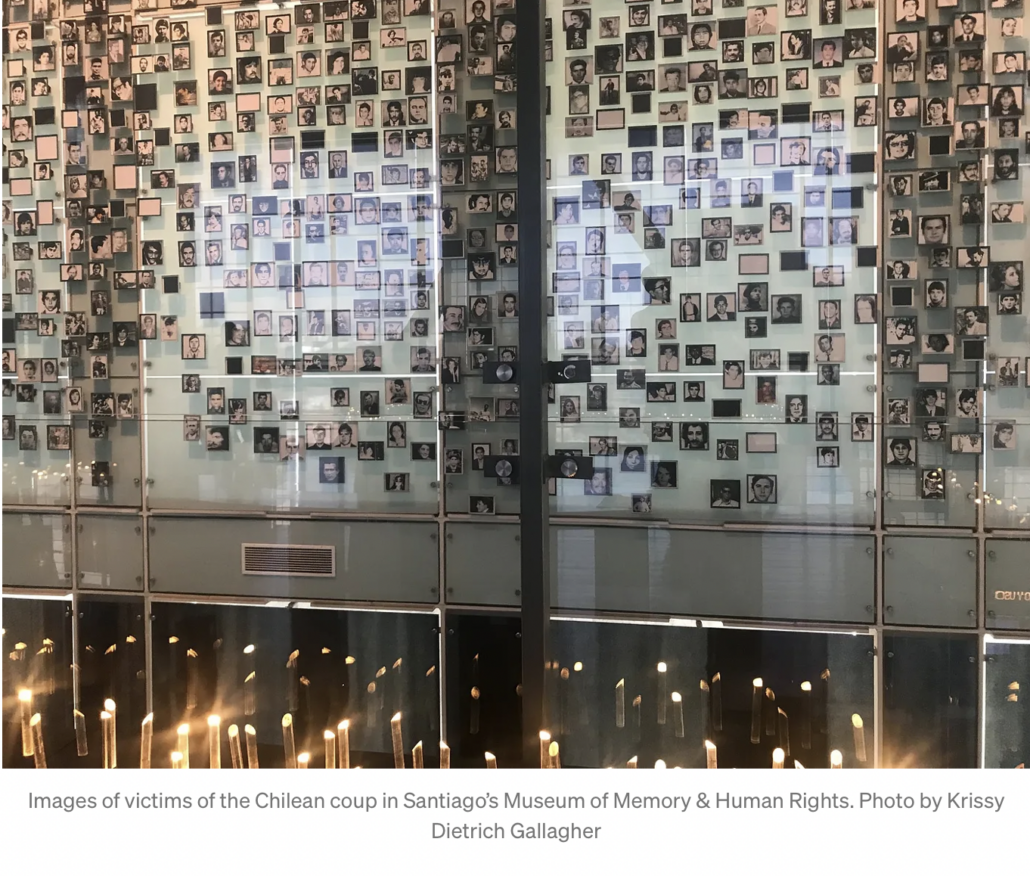

Thousands of Chileans were murdered or disappeared, tens of thousands imprisoned and tortured, and hundreds of thousands to millions exiled during the long dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet.

I’m not saying that’s what will happen here because I do not know what will happen here in the days between now and January 20, and I don’t know what will happen in the days and weeks and months to come.

But I do know that we cannot simply tell ourselves this will all be okay, things will go back to normal, we got this. Because nothing is normal and nothing should be normal and things have changed and things need to change. What happened at the Capitol this week, and what happened on the streets of our cities and towns all summer, and what’s happened over the past four years and the past 400 years, has culminated in a moment of reckoning.

What are our ideals? What do our democratic institutions really mean and who do they benefit? Who we are as a nation and as individuals, and, perhaps most importantly, who do we want to be?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!