Post-Mortem

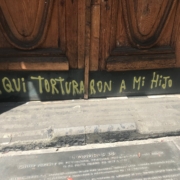

Well, it did not come to pass. The circle hasn’t been fully closed, Allende’s dying promise has not finally come true. Chile’s proposed constitution failed. And failed big.

It wasn’t actually a surprise that it failed since recent polls had increasingly showed discontent on behalf of the public. But the wide margin is surprising — and a big blow to the Left and President Gabriel Boric, who built his campaign on seeing this through.

There are plenty of people pontificating about how and why and what next and I will add my voice to theirs.

For one thing, the proposed constitution was just too damn long. It contained 388 articles. Compare that to the seven – seven! — in the U.S. Constitution. Now granted, ours happens to be rather sparse and, of course, required the addition of ten amendments before it could even be ratified. But Chile’s was seen as an overreach, the government meddling in tiny details of how people would live and vote and work and who could be elected to positions of power and what they could do with that power. Plus, as many journalists know, shorter is usually better. The draft was confusing and complicated and, in the eyes of many, overkill.

Along the same lines, all of the many, many mandates laid out in the proposed constitution would need to be enforced and evaluated and – big point here — paid for. It was never made clear who or how any of that would happen. Citizens feared huge tax increases to cover government oversight.

And, alas, the constitution was extremely progressive. If you know me, you know I think this is a good thing. I was in favor of the proposal and very much hoped it would pass, precisely because of the focus on the environment and gender parity among elected officials and legalized abortion enshrined right there in the Constitution and improved access to health care and higher education and affordable housing. But it was painted as radical overreach and scared many of the more moderate voters (more on that below) in what has traditionally been a pretty conservative, Catholic society.

All of the above points have been covered in numerous news outlets (at least the news outlets that cover Chile at all!). A few of my own more original thoughts:

I think it is easier to want something new when it’s an idea in the abstract than when it’s a real right-here-on-paper, warts-and-all option. The vast, vast majority of Chileans voted in October 2020 to replace the Pinochet-era constitution; 78% in fact! A new constitution was and is widely seen as long overdue. But that doesn’t mean that when it came down to what would actually be in that constitution, people would agree.

It’s sort of like when pollsters put a known politician up against “someone else” or “someone new” or “Candidate X” and most people pick the new, other, X-person. They have no faults, after all, because they don’t really exist. They could be any sort of candidate you might dream up and they’ve got to be better than the very real, very fallible politician standing in front of you.

But then, when that opponent is actually named, a real live person with faults of their own, the polls shift. “Oh wait, this person isn’t so perfect after all….”

The draft constitution was like that. People wanted something new, they wanted change – that they could agree on. But they could not agree on what the change would actually look like.

The other issue that we simply can’t ignore is that the opponents of the constitution, many of whom were against the entire rewriting and replacing process from the beginning, tend to be the people who traditionally hold power. The elites, the oligarchs, the politicians and media executives. In a dramatically unequal society (Chile boasts the third greatest social inequality on earth), a small number of families (by most accounts, seven) control not only the systems of power but also the access that the average person has to information.

The No voters in this case were able to hyperfocus on certain small points in the draft – such as a proposal that didn’t even make it in to the final proposed constitution to do away with the national Senate. It had indeed been suggested, but was quickly scrapped as being too extreme. But because a few proponents had spoken publicly in its favor, the opposition could use their words against them as proof of how far to the left they’d be willing to go. Get rid of the Senate?! … These people are in favor of anarchy! You shouldn’t trust them with our constitution.

Misinformation campaigns included the false claim that the new constitution would disarm the police (sound familiar?) and that private property would be seized (this too …?). Just like in the U.S., with rampant fears of gun-outlawing liberals and cries of “Socialism!” every time every time a politician utters a word in favor of equity, the right-wing media in Chile portrayed the most extreme aspects of the draft as guarantees. And as disastrous.

Those kinds of scare campaigns work. And they certainly did here.

One more thing, and I have no proof of this beyond an inkling, but I think the distrust of those in power that I mentioned above played a pretty big role in the final vote. When the protests started in October 2019, there was no leader. There was no politician and no party who had the support of the protestors. They were outsiders, largely powerless, voiceless citizens expressing their anger and frustration, their hope and determination.

Because those protests were so sustained (only stopping due to Covid shutdowns six months later) and because they were so successful (a right-wing president agreed to let the people decide whether to rewrite their constitution after all), many of those powerless, voiceless people became the people in power. Many of them were elected to the constituent assembly tasked with drafting the constitution. One of them was elected as the nation’s President.

This was what they wanted, of course, this was what people had fought for.

But the perception of power – and of those in power — is a dangerous thing. Especially in a society where distrust of elected officials runs so high. Those who had been on the outside, demanding a seat at the table, were suddenly on the inside, often at the head of the table. And so people began to distrust them. They lost some of their legitimacy in the process of becoming legitimate.

I’m not totally sure on that one as I’m not on the ground. I’m an amateur scholar from afar. But it does seem in keeping with Chilean temperament.

And now, they’ve got to accept this loss, dust themselves off and figure out what to do next. It is no doubt a blow to the progressive movement that was gaining such steam just a year ago. But the mandate still stands. The people voted to replace the constitution.

Just not with this one.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!