Why We Care About What We Care About

or What People Missed While Glued to #OceanGate (click on that pic above to see the full image)

This was certainly not in the list of things I had intended to write about. Words like “submersible” and #OceanGate and “catastrophic implosion” being nowhere near my most used on any given day.

And actually, that’s not really what I’m going to write about. I’m going to write about the 750 migrants from Syria, Pakistan, Egypt, Afghanistan, and Palestine who were traveling by boat—an “overcrowded fishing trawler”—from Libya to Italy to seek asylum as refugees on the same day that contact with the Titan was lost.

As the world became enthralled with the story of five billionaires trapped in a missing vessel of questionable design and as news outlets dedicated enormous space and attention to minute-by-minute updates and theories of their whereabouts and predictions of their survival chances and as governments dedicated millions of dollars and military personnel to their rescue, hundreds of men, women, and children seeking a better life were plunged into the depths of the Mediterranean Sea. And largely ignored.

I know, apples and oranges. They’re two totally different things. I know, we don’t control what the media focuses on or what people get sucked into. I know, it’s not just because they’re rich—we were obsessed with the trapped Chilean miners too. I know, one is completely compelling in a novel way (“Wait, he was navigating with a video game controller??”) and one is sadly commonplace.

But still. The fact that these tragedies unfolded on the same day. The fact that they both were “lost at sea.” The comparisons to the Titanic itself. The way one government jumped in to help and another bided their time, delaying their rescue and costing lives. We cannot not see this juxtaposition and wonder what it says about us. What we care about and why. Whose lives we value and whose we overlook.

While the final death toll off the coast of Greece is unknown, there were more than 750 people onboard that fishing boat and only 104 have been rescued alive. So chances are extremely high that we’re talking about nearly 650 bodies that have not—and likely never will be—retrieved from the waters. Survivors report there were 100 children caught in the hold of the boat. Sit with that for a moment.

Those people knew they were boarding a dangerous ship with the possibility of not making it to their destination. And yet, they did it anyway. Because they had to. Because the situations they were leaving behind were so horrific that a dangerous journey across the sea piloted by people they probably didn’t trust was preferable to staying.

While the others … well, the others were also heading on a dangerous journey through the sea piloted by a person they maybe shouldn’t have trusted. But for fun. For adventure. Now, I’m not wishing them death. I’m not saying they got what they deserved, not one single bit. Their lives had value too, I certainly hoped along with everyone else that they would somehow be found alive and brought to safety.

Heck, I have immediate family members who go off on crazy and often expensive adventures that could result in their deaths. My dad used to go cat-skiing in British Columbia and heli-skiing in Alaska and I’ve jumped out of an airplane fourteen times. If my brother got trapped in an avalanche while back country skiing, I’d want to launch a rescue mission too.

But I can’t help but look at how we care, how we compare, what grips us.

I think that sometimes it has to do with proximity, about who we relate to or see ourselves in. (Not sure how many of us relate to billionaires plunging themselves into the ocean depths, but still…) I’m definitely guilty of this approach to the world. When the November 2015 bombing in Paris took place, I was devastated. I, like so many others, wrote “Je suis Paris” on my Facebook page and posted old pictures of myself on the Eiffel Tower. Because I’ve walked those streets, I can picture it, it feels real to me. When the day before, a bomb had gone off in Beirut, I didn’t post anything at all, I didn’t say, “I am Lebanon” or stay glued to my television for news.

Was that the media’s fault? Were they not covering it enough for me to care? Or was that fault my own?

I wonder sometimes about assumptions of grief and suffering, whether expecting tragedy makes it more bearable. Is it sadder when a modern American baby dies of cancer than it was when an 19th century baby died of scarlet fever? Because one is expected and the other such a rarity? Does an American mother grieve harder when her 17-year old dies in a car accident than a Darfurian mother when her 17-year old dies as a child soldier? Because one is expected and one is a rarity? Because we get to birth children expecting them to lead full and healthy lives when others have no such privilege?

I’m willing to bet there was a father on that boat with his 19-year old son. Do we just assume (and accept) that because they’re war refugees from Syria, their lives are bound to be filled with suffering and tragedy? While we assume (and accept) that the billionaire businessman and his 19-year old son will have lives filled with success and adventure?

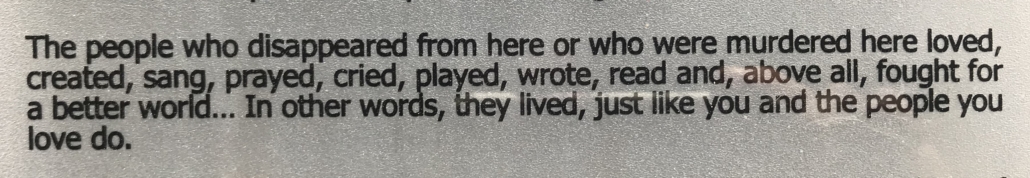

I don’t have answers to all of these questions. And I’m not shaming anyone for caring about the Titan and its occupants. But I am always reminded of this picture I took when visiting the memorial museum at Villa Grimaldi, one of the most notorious of Pinochet’s clandestine torture centers, located on the outskirts of Chile.

In other words, they were people, just like you. Even the billionaires seeking adventure. And especially the migrants seeking a better life.

Thank you for caring.